Iranian Tilework & Mosaic Art: History, Types, and Where to See Them

When we travel, we naturally want to understand what we’re looking at — not just walk past beautiful buildings, admire them briefly, and move on. Even without a guide standing next to us, it feels satisfying to recognize a few details on our own and connect more deeply with the place. While not everyone is an expert in art or architecture, learning a handful of simple points is easy — and surprisingly memorable. These small pieces of knowledge can completely change the way we see historical sites and make our experience far richer.

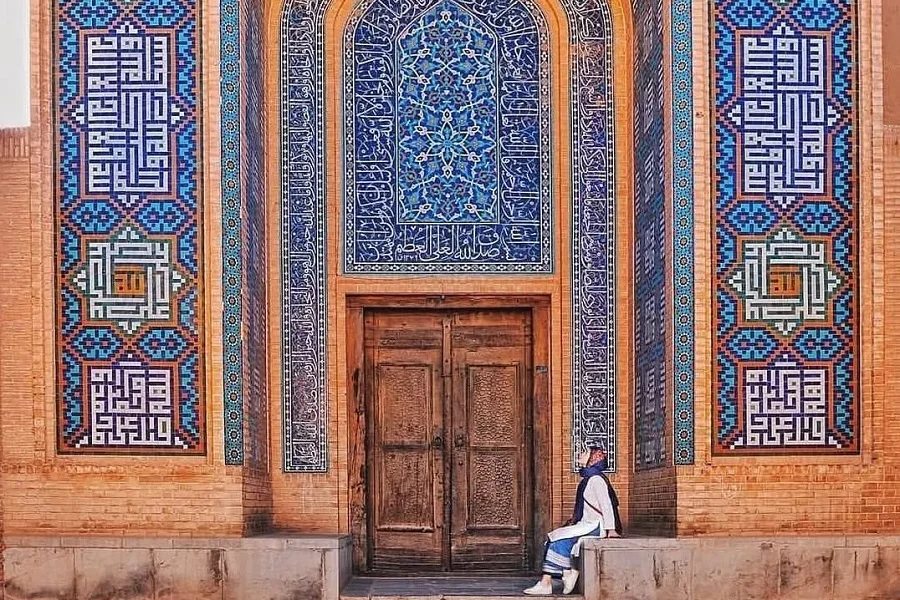

Iran is one of those countries where this kind of awareness truly matters. Its mosques, palaces, shrines, and even bridges are not only impressive in scale, but also full of meaning, symbolism, and artistic skill. One of the most striking elements you’ll notice almost everywhere is tilework. With just a little background knowledge, tiles stop being “just decoration” and start telling stories about history, belief, technology, and creativity.

That’s why in this article, we explore Iranian tilework in a clear and practical way — helping you recognize different styles, understand when and why they were used, and enjoy Iran’s architecture on a much deeper level during your travels.

What Is Tilework?

Tilework, in simple terms, is the use of glazed, baked clay bricks to decorate buildings. These tiles are not only beautiful but also practical: they protect surfaces, reflect light, and withstand heat. Behind this elegant art, however, lies a very long history.

The origins of tilework are closely linked to pottery — one of humanity’s oldest crafts. Long before tiles covered mosques and palaces, people shaped clay, fired it, and experimented with glazes. Over thousands of years, this basic skill evolved into increasingly complex and decorative forms. In Iran, tilework became one of the most important artistic languages used to express cultural identity, religious belief, and architectural beauty.

Early Roots: From Ancient Civilizations to Achaemenid Iran

Archaeological discoveries show that colored tiles in Egypt date back to around 4700 BC, proving how ancient this practice truly is. However, the earliest widespread use of glazed bricks is usually attributed to the Babylonians in the 2nd millennium BC.

In Iran, some of the oldest examples of tile-related decoration appear in Chogha Zanbil, a magnificent temple complex in today’s Khuzestan province. The glazed bricks found there date back to the mid-Elamite period (around 1250 BC) and already show a high level of craftsmanship.

Tilework reached an even higher level during the Achaemenid Empire. In Susa, the capital of Darius the Great, glazed bricks were used to decorate the famous Apadana Palace, depicting royal guards, animals, and symbolic motifs in vivid colors. These bricks were not merely decorative — they conveyed power, order, and imperial identity. Early examples can also be admired in Persepolis, where stone and glazed elements worked together to create a majestic visual language.

From Decline to Revival: Sassanids and Early Islamic Period

During the Arsacid (Parthian) era, the use of glazed bricks declined, and they were sometimes employed in more functional contexts, such as covering coffins. However, tilework experienced a revival under the Sassanids, who reintroduced decorative tiles in palaces such as Bishapur and Ctesiphon.

Sassanid tiles often featured human figures, musicians, floral motifs, and scenes from court life. These works reflected both artistic refinement and a vibrant color palette, showing that tilework was once again an important visual medium.

With the arrival of Islam, architectural decoration briefly shifted toward stuccowork, and tilework played a smaller role. But this pause did not last long.

The Seljuk Revival and the Rise of Monumental Tilework

During the Seljuk period, tilework returned strongly, especially in religious architecture. Turquoise tiles became a defining feature, often used on minarets and combined with inscriptions to make religious texts more visible from a distance.

Some fine examples from this era include the minarets of Sareban Mosque, Ali Mosque, and Sin Mosque. At this stage, tiles were still used selectively, not to cover entire buildings.

Creating full tile-covered monuments required both technical mastery and artistic confidence — and it took nearly two centuries to perfect this skill.

The Golden Age: 13th Century to Safavid Era

By the 13th century, Iranian craftsmen had mastered tilework to an extraordinary degree. Entire buildings were now covered inside and out. One of the greatest examples is the Sultaniyeh Dome, whose interior and exterior tiles represent a true milestone in architectural decoration. The portal of Sheikh Abd-os-Samad Khaniqah in Natanz is another masterpiece from this period.

During this time, geometric patterns were combined with floral designs, and new transparent glazes were developed. Cities such as Isfahan, Kashan, Yazd, and Kerman became major centers of tile production. The color palette expanded: green and brown appeared in Isfahan, while golden yellow emerged in Kerman.

The Timurid era introduced a strong preference for light and dark blue, a trend that continued into the early Safavid period. Cross- and star-shaped tiles became especially popular in Kashan, forming intricate floral and arabesque designs in mosques and tombs.

Under the Safavids, tilework became the main decorative element of Iranian architecture. Domes, iwans, prayer halls, and mihrabs were richly covered with tiles, especially in Isfahan, whose mosques remain some of the most breathtaking in the Islamic world.

Main Types of Iranian Tiles (Easy to Recognize While Traveling)

Zarrin-Fam Tiles

Known for their golden and green metallic shine, these tiles are created using a white glaze and metal compounds, then fired in a smoky kiln.

Common origins: Kashan, Rey, Gorgan, Saveh, Nishapur

Moarraq Tiles (Mosaic Tilework)

Made by cutting tiles into small colored pieces and assembling them like a puzzle to form large patterns.

Similar to European mosaics, but with different techniques.

Moaqalli Tiles

Created from very small tiles, often combined with bricks to prevent cracking.

Uses straight, diagonal, and checkerboard patterns

Commonly paired with Kufi script

Bena’i Tiles

Popular in the Safavid era, using triangles and squares to create bold geometric designs.

Famous pattern: Kand o Kalil

Mina’i Tiles

Mostly blue, decorated with floral and plant motifs.

Common in older buildings

Often used on exterior walls

Haft-Rang (Seven-Color) Tiles

A more practical technique was developed under Shah Abbas the Great and popular in the Qajar era.

Each tile contains the full design

Faster to produce, but less durable

Centers: Isfahan, Mashhad, Tehran

Final Thoughts: Seeing Iran with New Eyes

Understanding Iranian tilework transforms the way we experience historical buildings. Each tile reflects its time, its technology, and the hands that created it. Even basic knowledge encourages us to slow down, look closer, and truly appreciate the skill of past craftsmen — instead of simply passing by their work.

If you want to experience the full beauty of Iran’s architecture, from famous landmarks to lesser-known masterpieces, the local experts at Tours of Iran can guide you every step of the way. With their deep knowledge and carefully designed itineraries, you can visit Iran’s mosques, palaces, and historical sites with insight — and see the country not just as a destination, but as a living museum of art and culture.