Saadi Shirazi: A Timeless Persian Poet

When visiting Shiraz, one of the must-see attractions is the Tomb of Saadi, also known as Sa’diyeh. Saadi Shirazi, who was both born and buried in Shiraz, is regarded as one of the greatest poets in Persian literature. His work has left a profound impact on Persian culture and continues to inspire readers around the world.

He is renowned for his poetic artistry, the quality of his writing, and the profound social and moral insights in his work. These qualities have earned him the title “The Master of Speech.” Additionally, he is often referred to as “Sheikh” in recognition of his vast knowledge and wisdom.

April 21st marks the birth anniversary of Saadi Shirazi, celebrated across Iran, especially in Shiraz. If you’re planning a trip to Shiraz around this time, don’t miss the opportunity to join in the festivities. In this article, we’ll give you a brief introduction to Saadi and highlight some of his most popular works.

The Life of Saadi Shirazi

Saadi Shirazi, one of Persia’s most celebrated poets, was born in Shiraz during the 13th century. He adopted the name Saadi from the local prince Saʿd ibn Zangī. His exact birth year is uncertain, with some sources suggesting 1200, while others estimate it to be between 1213 and 1219. In his work Golestan, written in 1258, Saadi refers to himself as a 50-year-old who still feels naïve and lacking in life experience.

Saadi lost his father at a young age, but he fondly recalls childhood memories of attending festivals with him in his poetry. In 1225, Saadi left Shiraz to travel and explore foreign lands. This was during the time when the Mongols were invading the Fars Province.

After leaving Shiraz, Saadi enrolled at the Nizamiyya University in Baghdad, Iraq. There, he studied a wide range of subjects, including Islamic sciences, law, governance, history, Persian literature, and Islamic theology. In his poem Golestan, Saadi mentions studying under the renowned scholar Abu’l-Faraj ibn al-Jawzi.

The turmoil after the Mongol invasion of Khwarezm and Iran prompted Saadi to spend thirty years traveling abroad. He journeyed through Anatolia, where he visited the Port of Adana and met Ghazi landlords near Konya; Syria, where he noted the famine in Damascus; Egypt, where he described the music, bazaars, clerics, and elites; and Iraq, where he explored the port of Basra and the Tigris River. Saadi also traveled to Jerusalem and undertook a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina.

Saadi recounted an experience where he was allegedly captured by the Franks and put to work in the trenches of the Tripoli fortress, located in present-day Lebanon. However, this account, like many of his other “autobiographical” stories, is considered dubious.

Forced into isolated refugee camps for over twenty years due to the Mongol invasions, Saadi encountered a diverse array of people, including bandits, Imams, former wealthy individuals, military leaders, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens. He spent late nights in remote tea houses, engaging in conversations with merchants, farmers, preachers, travelers, thieves, and Sufi mendicants. This rich array of experiences deeply influenced his work, reflecting the struggles and suffering of ordinary Iranians during the tumultuous Mongol invasion.

Saadi eventually returned to Persia and reunited with his childhood friends in Isfahan and other cities. He made his way back to Shiraz before 1257 CE, the same year he completed his work Bustan. He was in his late forties at this point in his life. When he returned, Shiraz was under the rule of Atabak Abubakr ibn Sa’d ibn Zangi (1231–60), the Salghurid ruler of Fars.

He spent his final years in Shiraz, his birthplace, where he earned great respect from both the local ruler and the community. He died in Shiraz between 1291 and 1294.

Saadi Shirazi’s Writings

The key dates in Saadi’s life are linked to the completion of his two most renowned works: Bustan (The Orchard) and Golestan (The Rose Garden). Bustan was completed in late 1257, shortly after his return to Shiraz, and Golestan was finished in 1258, the following year.

Saadi was the pioneering Iranian poet to have his writings translated into European languages. André du Ryer made the first move in 1634 by translating parts of Golestan into French. This was followed by a Latin translation in 1651, and in 1654, Adam Olearius published complete German translations of both Bustan and Golestan.

The renowned German poet Goethe was inspired by Saadi’s works. He included adaptations of Saadi’s poems from Bustan and Golestan in his collection West-Östlicher Divan.

Golestan-e Saadi is a highly influential prose work in the Persian literary tradition. Dedicated to the Salghurid Atabeg of Fars, Moẓaffaral-Din Abu Bakr b. Saʿd b. Zangi, it is a collection of poems and stories known for its profound wisdom and frequent citation.

Bustan is a work written entirely in epic verse. It features stories that vividly illustrate the virtues valued in Islam, such as justice, generosity, modesty, and contentment. The text also offers reflections on the behavior and ecstatic practices of dervishes.

The Saadi Shrine also referred to as Sa’diyeh

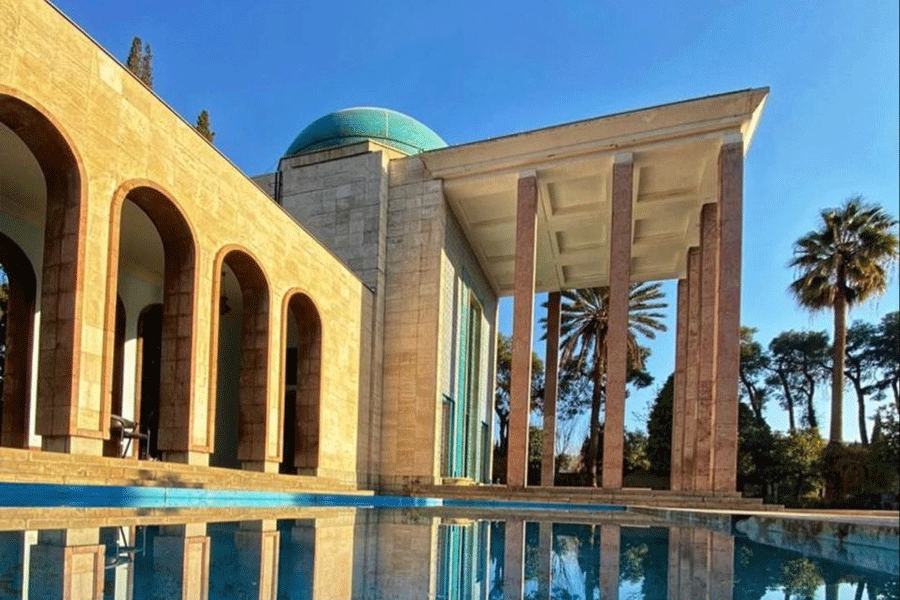

Located next to Delgosha Garden in the northeastern part of Shiraz, the Mausoleum of Saadi, or Sa’diyeh, was originally the monastery where Saadi spent the last years of his life.

Originally, Shams al-Din Muhammad Saheb Divani built a mausoleum over Saadi’s tomb. Ibn Battuta noted that visitors used to wash their clothes in a marble pond nearby, a tradition believed to have healing properties. This practice was common among the people of Shiraz even before the advent of Islam and possibly before Saadi’s time.

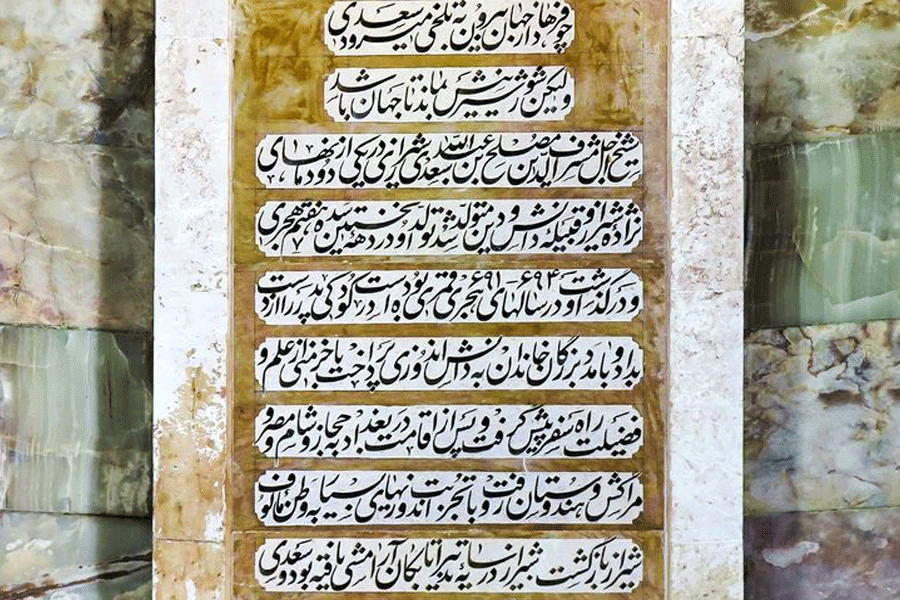

the monastery dedicated to Saadi was demolished by Yaghoob Zolghadr, the ruler of Fars in 1589 (998 AH). Muhammad Taghi Behrouzi suggests this destruction was due to Saadi’s Sunni affiliation. Later, Ali-Akbar Ghavam al-Mulk Shirazi, a distinguished Shirazi scholar, replaced the original tombstone with a new one featuring an inscription from Saadi’s Bustan. This revised tombstone has been preserved to the present day.

during the reign of Karimkhan Zand(In 1773), a magnificent mausoleum made of plaster and brick was constructed over Saadi’s tomb. The building featured a hallway on the lower level. To the east of this hallway was Saadi’s tomb, enclosed by a wooden cover, while another room on the west side housed the remains of Shoorideh Shirazi, a blind poet from Shiraz, as per his wishes. The upper floor mirrored the layout of the lower level, but in deference to Saadi, no room was built above the eastern room where his tomb was situated.

Saadi’s mausoleum received attention during the Qajar Era, undergoing restoration. Later, Habib Allah Khan Qavam al-Mulk ordered further repairs and restoration of parts of the mausoleum.

It was in 1949, architects when Mohsen Foroughi and Ali Sadeghi were commissioned to design a new mausoleum for Saadi. Construction began in March 1951, with the design taking inspiration from Isfahan’s Chehel Sotoun Palace and combining modern and classical architectural elements. The mausoleum, surrounded by a 7,700 square meter garden, was completed in 1953. It was officially reopened to the public with a ceremony attended by Minister of Culture Mahmoud Hesabi and Ali Asghar Hekmat. On the same day, a statue of Saadi, sculpted by Abolhassan Sedighi, was unveiled at the gate of Isfahan.

The dome of the mausoleum is adorned with turquoise tiles, while the base is constructed from black stones. The columns and the front of the porticos are made of red granite. The facade of the mausoleum is covered in travertine, and the interior walls are finished with marble. The tomb is centrally located within an octagonal structure. On seven sides of the mausoleum, inscriptions of Gulistan, Bustan, and Saadi’s mono-rhyme poems (Qasidas), written by Ibrahim Bouzari, are displayed. Additionally, an inscription by Ali Asghar Hekmat details the construction of the tomb.

The main entrance to the garden, designed by renowned architect André Godard, features a verse by Saadi. In front of the portico, there is a pond where visitors toss coins in hopes of making their wishes come true. An underground aqueduct, or qanat, with a depth of 10 meters, flows beneath the garden and feeds into the fish pond.

On the left side of the mausoleum, there’s an octagonal fish pond. It is believed that Saadi originally had small marble ponds near his hermitage. The pond’s tiling, which is characteristic of the Seljuk period, was designed by the renowned tiler known as “Tirandaz” and executed by the Cultural Heritage Organization in 1993.

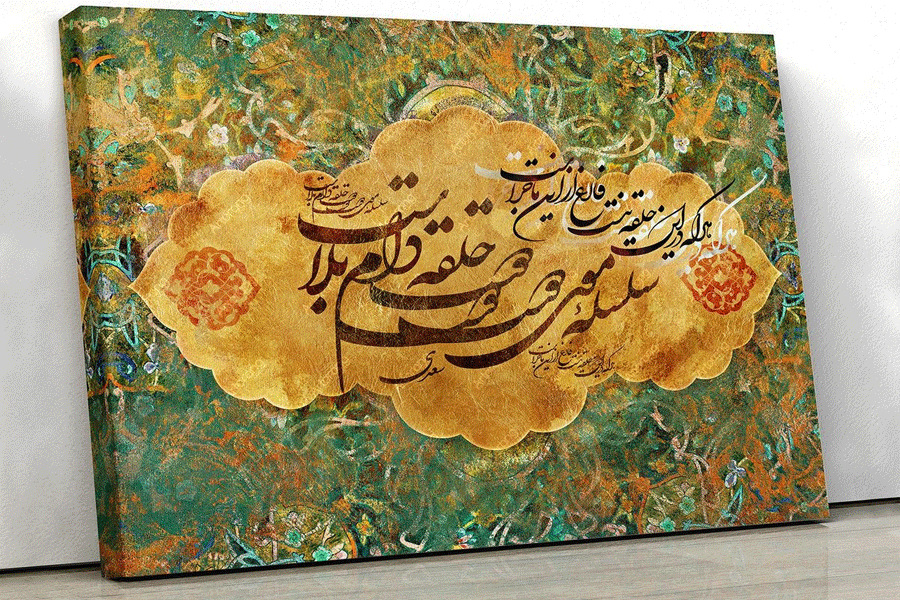

Of one Essence is the human race,

Thusly has Creation put the Base;

One Limb impacted is sufficient,

For all Others to feel the Mace.